Why the Dalai Lama Continues to be a Counselor to Us All

No sooner had a tsunami, in March 2011, swept 18,500 souls to their deaths in Japan than the Dalai Lama, in his home in northern India, expressed his determination to make a “pilgrimage” to offer what he could to the devastated area. Before the year was out, I was accompanying him to Ishinomaki, a fishing village almost entirely leveled by the disaster. I’d met him first as a teenager and had already been speaking regularly with him for 37 years, as well as published a book on his work and his vision.

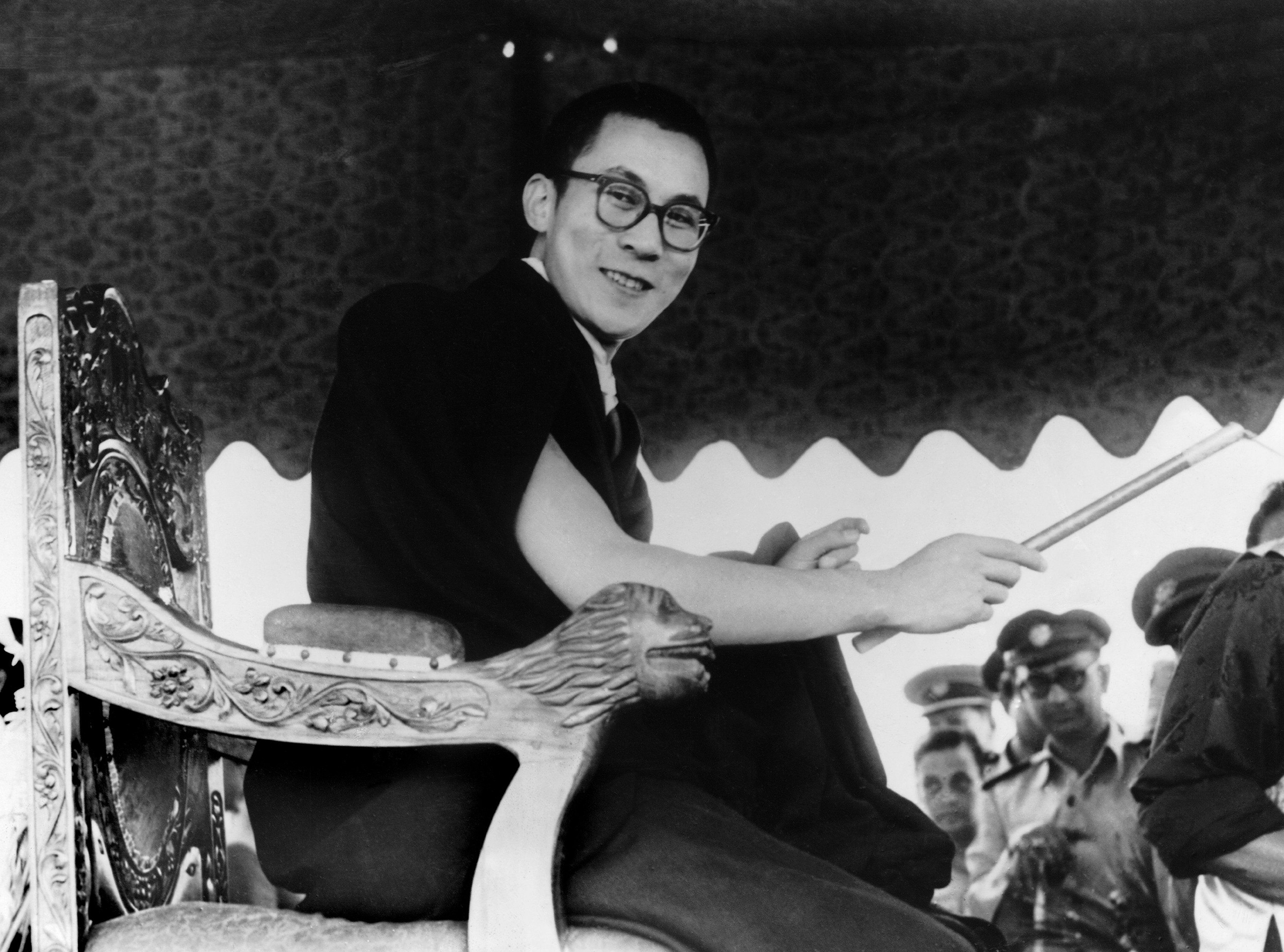

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]The minute his car came to a halt amidst the debris, the Tibetan leader strode out and offered blessings to the hundreds lined up along the road, together with words of encouragement. He held heads against his heart, trying to soothe tears. Then, in a nearby temple that had somehow survived the cataclysm, he recalled his own sudden flight from Tibet in 1959. No life is without loss, he observed—but renewal is an hourly possibility.

That morning is a tiny reminder of how, as he prepares to mark his 90th birthday on July 6th, the 14th Dalai Lama has come to symbolize a sort of planetary doctor of the mind, making house-calls on every continent. Regularly noting that “my religion is kindness” and frequently reiterating that if scientific findings contradict Buddhist teachings, science must trump Buddhism, he’s become the rare spiritual teacher who can speak across every border in our ever more divided world.

In an age when moral leadership can be hard to find, he’s become a voice of ecumenical wisdom and compassion to whom millions from every tradition can turn, for both solace and guidance.

Read More: A Monk’s Struggle

Born in a cowshed in a village three hours from the nearest road, Tenzin Gyatso, as he became known, is the first Dalai Lama to set foot outside of Asia. He often says that while having lost his home after he had to leave Tibet—to prevent outright war against China—he’s gained the whole world as his home. Having traveled with him everywhere from Okinawa to L.A. and Jaipur to Zurich, I can see that’s no idle claim. Here is a Buddhist leader who delivers talks on the Gospels to a group of Christians, tears misting his eyes as he describes some of Jesus’s parables. Here, too, is a champion of “secular ethics” who calls himself a “defender of Islam,” consults rabbis on how to sustain a culture in exile, and regularly refers to himself as a student of India, the predominantly Hindu country where he has lived for 66 years.

This would be liberating in any circumstance, but it offers an especially powerful example at a time when so many of us are torn apart by competing belief systems. Over half a century of talking with him, I’ve noticed how the Dalai Lama’s first impulse is to find common ground with every child—or soldier, or Chinese Communist party member—he meets. He begins each day with prayers for his “Chinese brothers and sisters,” taking care to distinguish between often heroic individuals and a government in Beijing that has more or less tried to destroy Tibet. And though he’s one of the world’s most respected religious leaders, he notes that religion is a luxury, like tea, that adds savor to life. But the water that none of us can live without is everyday kindness and responsibility.

Above all, he’s a master realist; as leader of his people since the age of four, he has no interest in impractical schemes or romantic gestures. He knows that, in the 8th century, Tibetan troops captured the Chinese capital, Chang’an, while at other times, China has almost erased Tibet. No border lasts forever. For 10 recent Novembers, I traveled across Japan with him, spending every moment of his working day by his side; what moved me most deeply, every year, was when we stepped into a room full of ragged, sobbing figures, and I realized that every one of them was Han Chinese, from the People’s Republic, depleting hard-earned savings to come to Japan to listen to the Dalai Lama.

For Buddhists, he is a formidable scholar who draws on ancient texts to show that people’s interdependent destinies make environmental awareness and global consciousness a necessity. For Tibetans, he has become one of the three defining Dalai Lamas of their history. But for the rest of us, he’s been an open-hearted incarnation of conscience who puts his faith in “common sense, common experience, and scientific findings.” A natural democrat, he renounced all temporal power in 2011, though his people often wish he’d make all their decisions for them. He has also often stated that he may be the last Dalai Lama—though not the last spiritual leader of the Tibetans—since, on his death, Beijing will surely choose a boy who’s a Party member and present him as a successor.

It’s a curious paradox in his life that he has set up Tibetan monasteries and communities in India and across the world, even as Tibet itself is ever more eroded by foreign settlers and murderous policies. He has inspired confidence in many countries, even as his own people, in their suffering, are driven to self-immolation and calls for armed resistance. And he’s become a beloved visitor to almost every continent, even though unable to return to his homeland. Yet one of his sovereign gifts, in our short-attention age, is for never losing sight of the larger picture.

The day after he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace, in 1989, I barged in on him with questions on behalf of this very magazine. Though Tibetans across the globe were celebrating the victory, the Dalai Lama was, as ever, more measured and far-sighted. He really wondered if he’d done enough, he told me, but all he could do was give all of himself, day after day, in the knowledge that in the long run—as his peers and teachers, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King knew—the moral universe bends towards justice. Ninety years from now—and in centuries to come—he will be remembered as one of our first global spiritual leaders, and one of the most enduring.